A professor and a teacher: the role of Jules Chauvet and Jacques Néauport in Natural Wine.

In this post, I will address two influential figures in the history of modern natural wine: Jules Chauvet, the Chemist, and Jacques Néauport, the Evangelist. Their contributions have significantly shaped the movement, and understanding their roles is essential for understanding today’s natural wine.

Jules Chauvet was born in 1907 in a small village of the Beaujolais region, from a family of wine merchants who farmed six hectares in Beaujolais-Village. He started working in the family wine business before the Second World War.

He dedicated himself to the study of chemistry at the “Institut de Chimie" in Lyon. During his time there, he befriended the German Nobel Prize winner Otto Warburg and collaborated with him in Berlin.

During World War II, he was imprisoned in Germany but successfully escaped and returned to Beaujolais for the harvest. He held a negative view of anything associated with the Nazis, including biodynamic practices. Although the Biodynamic Reich Association was banned in 1941, there were still some connections to the Nazi regime.

His area of expertise was wine biochemistry. He published several scientific papers on yeast and various aspects of fermentation in wine, covering topics such as malolactic fermentation and carbonic maceration.

He was an exceptional wine taster, regarded as one of the most talented and respected in his field. His wine-tasting philosophy emphasized tasting in solitude, believing that the reactions of others should not influence your judgement.

He possessed an incredible sense of smell; he was able to recognize indescribable flavors, such as Russian leather, which can be found in rare, fine wines.

Flavors were so important to him that he instigated the classical wine glass, known as the ISO or INAO glass. Today, the ISO/INAO glass remains the global standard.

You can find his dedication to fine wines in his speech to young winemakers in Mâcon in 1950, “L’arôme des vins fins”. In this text, you can understand that if wine is a mysterious beverage, its aroma comes from the field and the vinification.

As a winemaker, he incorporated findings from his research into his practice. He chose to use natural indigenous yeasts instead of industrial varieties.

Additionally, he rejected chaptalization, which involves adding sugar to the must to increase alcohol content, and he avoided adding sulfur dioxide (SO₂) to the must in order to preserve the natural yeast.

In the field, no fertilizer, special vine pruning, and manual harvest to select the best grapes only. He was one of the first winemakers to make wine without using sulfites in the 50’s.

Making wine this way was revolutionary; it was the first modern natural wine. More revolutionary for this time, the idea was that the quality of a wine should be judged by its taste rather than its alcohol level.

But as revolutionary as he was, Monsieur Chauvet was respected by his peers. His wine could be found in one of the most prestigious locations in France, the cellar of the Palais de l’Élysée (the French presidency).

Jules Chauvet passed away in June 1989, leaving behind an impressive archive of his wine research. Some of his texts were published posthumously.

However, Jules Chauvet’s impact extends beyond his research and winemaking techniques; his door was always open. Winemakers could always ask for advice, but he was assertive about how to conduct a vineyard and how wine should be made.

A lot of winemakers came to see him: the first wave of the French (and not French) natural winemakers, some well-known winemakers.

Chauvet built the science; one man set out to spread it far and wide. Enter Jacques Néauport.

Jacques Néauport wasn’t a winemaker; he was born in the north of France, a region better known for beers. He discovered wine with his maternal uncle, who lived in Ardeche and had a wine cave that fascinated him as a child.

To earn money while studying, he worked at wineries across France, picking grapes and sorting bottles. It was during this time that he became friends with Marcel Lapierre, who would later emerge as a prominent figure in the first wave of natural winemakers.

After graduating from university, he became an English teacher. He moved to the UK to teach French and, as he says himself, he had a lot of free time which allowed him to read extensively about wine.

He had an ambition to write a book about wine. He began working with winemakers across France and Europe. Inspired by the “Real Ale” movement (where English people praised non-industrial beer), he published, in English, “Real Wine”.

He never owned a car or a driver’s license. For years, he has traveled from one winemaker to another by hitchhiking, train, or bus. He learned the craft of winemaking, built a network, and made friends. In 1975, he started making wines without sulfites in Jura.

In 1980, he won a nation wide wine tasting contest organized by “La Revue des Vins de France” the largest wine magazine in France, and enrolled in a wine school in Bourgogne.

In 1981, he started an internship at Jules Chauvet’s winery while working with Marcel Lapierre a few kilometers away. Working with Chauvet was a great opportunity to understand wine like no one before. Chauvet could answer any of his questions with articles, references or books.

He has the idea to bring his winegrower friends to see Jules Chauvet and talk about vinification, sulfite, and chaptalization. That’s how Marcel Lapierre, Jean Foillard, Georges Descombes, and many others discovered the works and advice of Jules Chauvet.

He then worked, as what we will call today, a consultant, helping countless winemakers to redefine their wines and their process. He put Jules Chauvet’s principles into practice with Marcel Lapierre, Guy Breton, or Yvon Metras. He continues his work with the younger generation of natural winemakers in the 90s, Le Mazel, Chateau Saint Anne, and Le Clos du Tue-Boeuf.

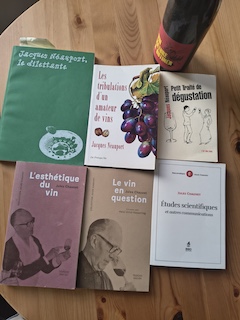

His remuneration for his work became a source of tension between Jacques and some winemakers. In 1999, he published an autobiographical story, “Les tribulations d’un amateur de vins”. The book is a gold mine for anyone who wants to understand the beginning of the natural wine movement, but it also settles some scores with some winegrowers, including Marcel Lapierre. They never spoke to each other again.

Today, Jacques Néauport continues to offer advice to young winemakers while living with his mother in Ardèche. He still does not have a driver’s license and does not own a smartphone, much less an Instagram or Facebook account. Outside the natural wine community, few people know of him.

Together, Chauvet’s lab-tested principles and Néauport’s roaming evangelism established the foundation for the natural wine movement we enjoy today. Without them, the movement could be vastly different, leaving us wondering what wines we might be drinking instead.

It doesn’t mean that nothing occurred without them. Some winemakers, without knowing Jules Chauvet, initiated natural wine production without the assistance of Jules Chauvet or Jacques Néauport, but they started a movement.

– You can learn more about Jules Chauvet on this site