natural wine: from the origin

Most people agree that the expression natural wine emerged in France in the latter half of the 20th century. Initially referred to as vin naturel and later evolved into vin nature.

some linguistics considerations

In French, when two words follow each other, the first is a noun, and the second is an adjective, it, normally, clarifies the noun, while with natural wine, we are still a little in the dark. The history of modern natural wine can teach us a lot more about the significance of this expression.

a modern origin

Many wine authors, bloggers, and experts claim that the expression “natural wine” was first forged in the latter half of the 20th century. Indeed, during the 1990s the term began to designate wines made without additives. However, this was not the first time the phrase appeared in France to denote wine produced without additives. The expression “vin naturel” was recorded as early as 1907, though its original usage carried an unexpected nuance.

from a revolt to a legal definition of wine

At the beginning of the 20th century, the wine scene was different from what it is today. In France, wine was not merely a beverage; it was a part of the daily food ration. While Europe began to recover from the phylloxera crisis, the working class enjoyed a more varied diet that now included meat, bread, and, of course, wine.

However, the fragile balance between production and demand was soon disrupted. The area under vine cultivation increased in the Languedoc-Roussillon region, compounded by substantial imports from Italy, Spain, and Algeria. The exceptional production years of 1904 and 1905 signaled the onset of an overproduction crisis.

During this period, wine was primarily sold in barrels rather than in bottles, and some merchants did not hesitate to tamper with their product, diluting it with water and sugar, occasionally even adding dried raisins—to extend their supplies.

This overproduction crisis caused significant social and economic difficulties, particularly in the South of France. At the beginning of the 20th century, widespread unrest erupted in the form of revolts. Massive demonstrations emerged—one of which saw nearly 800,000 participants—accompanied by riots that left many dead and wounded.

While the crisis had multiple causes, one of the rallying cries was Vive le Vin Naturel (“Long live natural wine”), a slogan that vociferously opposed the adulteration practices employed by some merchants. For the first time, wine was defined as “natural,” establishing a principle that any tampering or dilution of the product should not be tolerated. In the wake of this rebellion, the government wrote a legal definition of wine: “No beverage may be held or transported for sale, or sold under the name of wine unless it comes exclusively from the alcoholic fermentation of fresh grapes or grape juice.”

The desire to craft wine just as our grandparents did, we hear today about natural wine come from here, the South of France, the very elders—our grandparents—embodied this tradition by championing winemaking methods rooted in authenticity. For them, vin naturel was not so much a reference to an unadulterated natural process but rather a stance against the artificial wines produced by adding sugar, dried raisins, and water.

the scientist that becomes the father of natural wine

Several years after the revolt, the world saw a profound transformation with the start of the Green Revolution. This agricultural upheaval introduced mechanization, artificial fertilizers, phytosanitary products, and all the techniques that have come to define today’s agriculture.

The wine industry was not immune to these changes. Innovations such as industrial yeasts, chemical additives, and other industrial methods became standard practices. This period also witnessed the birth of modern enology, driven by the principles of applied chemistry and new fermentation techniques that have long been foundational in winemaking education. Simultaneously, the rise of supermarket and mass consumption reshaped the marketplace. In the 1950s and 1960s, two main categories of wine emerged: the mass-produced industrial table wine and the fine wine. Yet in many cases, both types were produced using the same industrial processes.

It was within the realm of fine wine in the 1960s that the expression vin naturel re-emerged not from radical innovators, but rather from a notably conventional figure. Here’s come Jules Chauvet, a scientist and wine merchant from Beaujolais. Born in 1907 into a family of wine merchants, Chauvet pursued studies in chemistry and biology at the University of Lyon before further refining his expertise under the guidance of the renowned German Nobel laureate, Otto Warburg.

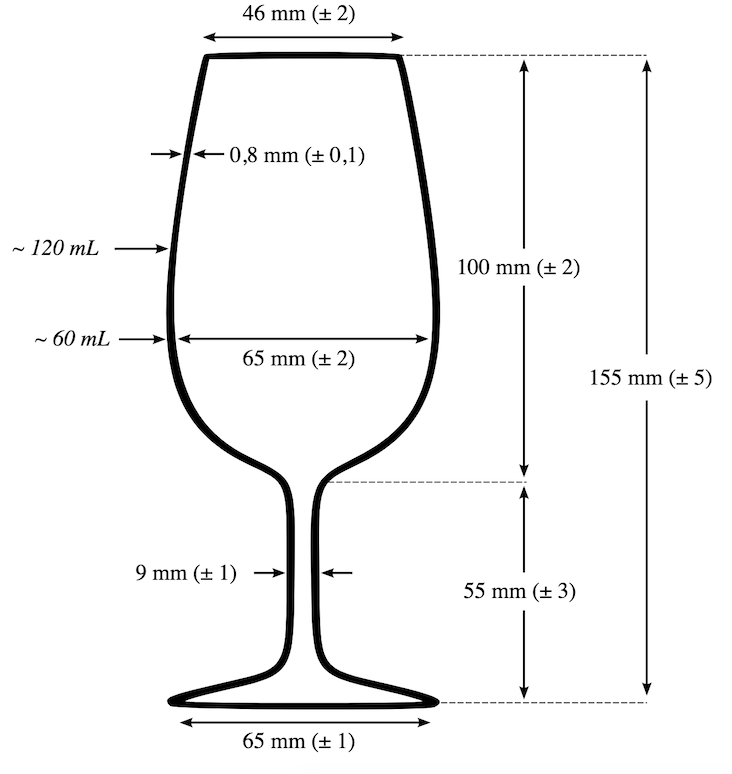

He was regarded as one of the most renowned wine tasters of his time. His research spanned a broad spectrum of topics within the wine world. Notably, he authored a famous paper —The Physical Chemistry of Surfaces and the Aroma of Fine Wines— which explored how the shape of a wine glass influences aroma and ultimately led to the creation of the INAO/ISO wine glass design used everywhere today. His meticulous work also included an extensive inventory of the wild yeasts of Beaujolais, as well as groundbreaking studies on malolactic fermentation and carbonic maceration.

Aa a winemaker from a generation when chemicals were not widely used, he was equally a dedicated educator in fine winemaking. Among his many memorable teachings, he would often say, Faites un vin naturel avec un joli parfum (Make a natural wine with a nice aroma).

In 1951, he emerged as one of the first modern winemakers to successfully produce wine without added sulfite, marking a significant milestone in the evolution of natural winemaking techniques.

At the time, his ideas were considered heretical, yet they were truly revolutionary: he asserted that the aroma of fine wine comes from the vine’s terroir and its wild yeasts—not from additives or other artificial enhancements. In his view, phytosanitary products kill the very microbes and wild yeasts that are essential for building the wine’s character, forcing winemakers to rely on industrial yeasts, sulfur dioxide during fermentation, and other things. Moreover, sulfur dioxide not only masks some of the wine’s delicate aromas but also destroys the yeasts and microbes responsible for synthesizing those nuanced flavors.

Jules Chauvet rarely used the term Naturel to describe wine; instead, he emphasized its purity or harmony as a direct opposition to wines adulterated with additives. However, in a seminal article titled “La vinification rouge,” published in the magazine Le Bourguignon Viticole in 1960, he noted, On obtient alors un vin naturel recherché par le consomateur avisé (we then obtain a natural wine sought after by the informed consumer).

The implications of Chauvet’s research are significant. If natural yeasts and terroir are the keystones of fine wine production, then vine growers and winemakers must safeguard these microorganisms, both in the fields and in the cellars. Moreover, if the health of vine roots is essential for creating quality wine, the use of artificial fertilizers should be strictly limited. This philosophy forms the bedrock of natural wine—a foundation that Jules Chauvet gradually forged through decades of study and experimentation.

precursors, Marcel Lapierre and the Beaujolais team

Though often labeled a heretic for his unconventional views, Chauvet was also a passionate educator who welcomed young winemakers into his fold. One of the first to carry forward his legacy was Jacques Néauport, who pioneered natural winemaking outside of Chauvet’s cellars. Then, in 1980, Chauvet’s influence expanded further when he met Marcel Lapierre, a young winemaker from Beaujolais and a friend of Jacques Néauport. Their encounters not only underscored his influence but also helped usher in a new era of natural wine production.

Jacques Néauport uncovered his passion for wine during holidays in England as a student. His enthusiasm led him to Beaujolais, where he met Marcel Lapierre and began making wine alongside friends. In 1975, in the Jura, he produced his first wine without sulfur dioxide. In 1980, he won a prestigious tasting competition organized by La Revue des Vins de France. Following this achievement, he apprenticed with Jules Chauvet, deepening his expertise and later becoming a sort of consultant for natural winemakers, going from cellar to cellar to diffuse his expertise.

Marcel Lapierre remains a famous name in the natural wine world. In the 1970s, he took over his family’s vineyard and initially produced wine using the conventional methods taught in winemaking schools—methods that relied heavily on chemicals and sulfites. However, his curiosity drove him to seek an alternative approach. Crucially, he meticulously documented his journey in notebooks while traveling extensively across France to explore different winemaking techniques. In 1980, Lapierre met Jules Chauvet, whose scientific insights inspired him to produce his first wine without added SO₂. This breakthrough marked a pivotal step toward expressing the true character of the terroir through natural fermentation.

Later, Lapierre joined forces with fellow Beaujolais winemakers Jean Foillard and Guy Breton. Their collaboration laid the groundwork for what would eventually blossom into the natural wine movement. Together, they championed a philosophy known as Vin tout raisin (all-grape wine), emphasizing that the finest wines should be made solely from grapes—without the interference of additives or artificial interventions.

The path to adopting this new way of winemaking was far from easy. The weight of entrenched traditions, institutional pressures, and the scrutiny of their peers could easily have forced many back into producing conventional wines. Nevertheless, the members of this avant-garde group were true rebels in the alternative scene—so much so that Marcel Lapierre himself counted among his friends the progressist philosopher Guy Debord.

However, not all winemakers who sought unadulterated wines shared this countercultural political vision. While many longed for wines that were unaltered, their motivations and worldviews could differ considerably.

At the same time, Jacques Néauport took it upon himself to pass on the insights he had gained from Jules Chauvet. He worked with several winemakers, among them, Pierre Overnoy in the Jura, Ulrich Kesserling in Switzerland, Thierry Allemand in Cornas, and the team at Domaine de Mazel in Ardèche to teach them the art and science of producing fine, unmanipulated wines.

But one thing united these two groups: their shared opposition to the dominance of technical, industrial winemaking. In the 1980s, France actively promoted industrial wines—primarily to boost export revenue, leaving little room for alternative winemaking approaches.

Paris, pioneer in natural wine bars

In this atmosphere, the first bars serving wines from Marcel Lapierre, his group, and other alternative winemakers emerged in Paris. A fundamental change helped make this possible. Before the 1970s and 1980s, winemakers typically sold their wine in bulk to merchants. However, beginning in these decades, bottling at the vineyard became the norm, allowing consumers to more easily identify individual wines and enabling winemakers to sell directly to bars, wine cellars, and restaurants.

One such bar was located near the city hall in the 5th arrondissement of Paris, adjacent to the Panthéon and Sorbonne University. Le “Café de la Nouvelle Mairie” was a typical French bistro serving traditional dishes alongside wines from Beaujolais, including those produced by Marcel Lapierre and others.

Although it may not have been the very first establishment to serve these alternative wines, it is perhaps the most frequently cited. Situated near the vibrant and popular Mouffetard, it became a place where many people discovered this innovative approach to winemaking.

However, it was in another part of Paris that these wines truly gained fame. Paris is divided by the Seine into two distinct halves—the right bank and the left bank. The right bank, known for its vibrant and rebellious spirit, became a bed for alternative wine culture. In the neighborhood adjacent to Belleville, on rue des Envierges, a wine bar called Le Bistrot Envierges opened its doors, specializing in alternative wines. This trend soon spread throughout the district during the 1980s, with establishments such as Le Baratin,still open in the Belleville area, and l’Ange Vin, which was launched in 1987 and managed by the artist Jean-Pierre Robinot.

Jean-Pierre Robinot, together with journalist and wine critic Michel Bettane, went on to found an ad-free wine journal, Le Rouge et le Blanc, a publication that continues to be published today.

the seconde vague

In the 1990s, an increasing number of bars, bistros, and restaurants began featuring these alternative wines. More winemakers embraced the new approach—not only in Beaujolais but also across France, Italy, and Switzerland. Even the production of Beaujolais Nouveau, then considered the most industrial wine, started to incorporate these natural principles. Marcel Lapierre and Jean-Claude Chanudet assumed control of the Château Cambon domain and produced the first Beaujolais Nouveau without using artificial yeast.

By the late 1990s, the stage was set for the inaugural natural wine salon in a Bourgueil cellar, known as La Dive. This event provided a vibrant window into a new era of winemaking—one that championed authenticity and the rejection of artificial interventions. La Dive is today the reference for natural wine fairs.

how to find a name, semantic and linguistic

There is no official term for this winemaking style. Several names have been proposed over the years. In French, the adjective Naturel was initially considered. However, due to the risk of confusion with Vin doux naturel (naturally sweet wine), a different adjective was preferred. Thus, Nature was adopted to signify a wine made without any additives, rather than to evoke nature in the sense of “mother nature”, much like in Yaourt Nature (plain yogurt), which contains no sugar, flavorings, or other ingredients.

Other alternatives were also proposed, such as Vin nu (naked wine), vin vivant (living wine), and vin sincère (sincere wine). Nevertheless, since the early 2000s, the term Nature has become the most widely used.

Since the early 2000s, natural wine has experienced an explosion in popularity. More winemakers have embraced this approach, and the number of wine shops, salons, and bars dedicated to natural wine has grown around the world. Today, you can have a natural wine glass in a bar in Bali or Thailand, and even find bottles in some selected supermarkets—an indication of how far the movement has come compared to when a natural wine bar was a rare sight in 1990s Europe. With salons and wine fairs now taking place globally, it wouldn’t be surprising to see natural wine even reaching space in the coming years.

conclusion

As you can see, despite claims from some people, that natural wine is just a temporary trend, it has a rich and deep history. Its roots can be traced back to the French riots of 1900, to Jules Chauvet’s pioneering vinification using natural yeasts—without the addition of sugar or SO₂—and to the later movement of the late 1970s that championed making wine purely from grapes.

The history of natural wine tells us much about its philosophy and the people behind it. Removing SO₂ is not an end in itself but rather a consequence of a commitment to preserving the natural microbial life in the vineyard. To produce a fine wine, winemakers must nurture healthy vines with strong roots and rely on the natural yeasts that present in the environment—which means avoiding herbicides, pesticides, and the early use of SO₂, all of which can disrupt the natural fermentation process. Unlike biodynamic methods, this approach is firmly grounded in science rather than rooted in esoteric practices.

Initially, many winemakers in this movement came from an alternative, even rebellious, background—heavily influenced by the work of Jules Chauvet. Yet not all were radical reformers; some simply continued long-standing family traditions of making wine solely from grapes.

Today, natural wine is everywhere. It’s now so widespread that even its detractors may praise a “natural wine bottle” without realizing they are endorsing a product with a rich, storied history.