From the phylloxera crisis to natural wine

The phylloxera appears in Europe during the second part of the 19th century and destroy a major part of the European vineyard. The first apparition of what we call natural wine dates back to the sixties. At first, these two elements seem unrelated, but they are more related than you can think.

Let’s talk about vine anatomy to start, a vine plant is composed of a wooden part, the stump, the roots, and an aerial vegetal part. Before the phylloxera crisis in Europe, the species used in Europe was Vitis Vinifera, and there were much more varieties than we have now. Then come Phylloxera in the late 19th century. Phylloxera is a bug parasite from the east part of the United States. It can infect the vegetal part of the plant but also its roots. If the infection is limited to the leaves, the harvest may be lost but if the bug manages its way into the soil and enters the roots the plant is condemned to death within 3 years.

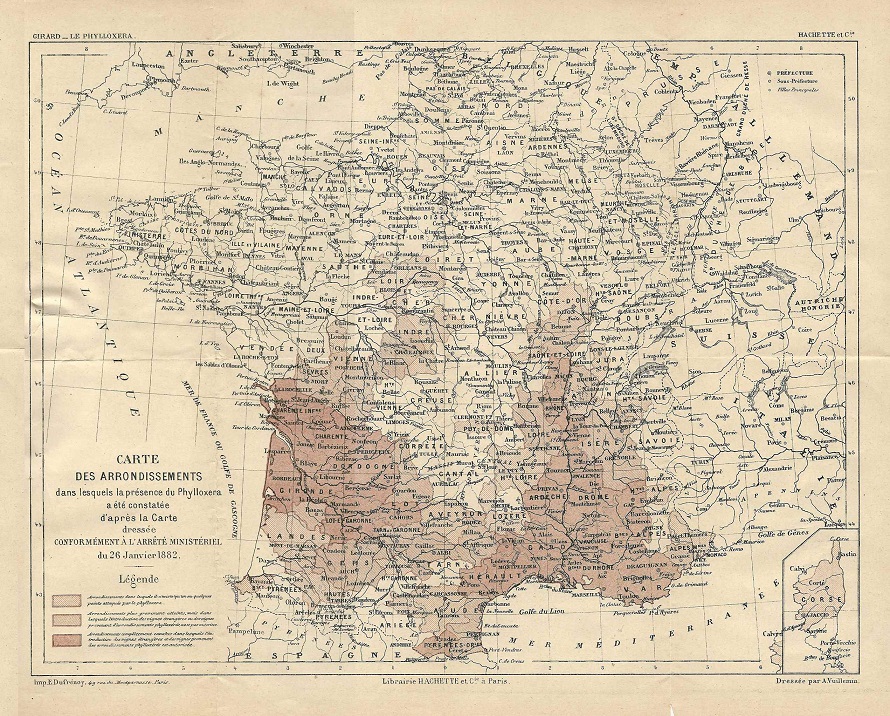

The first vineyard to be devasted by the plague was in the southern part of the Rhône valley in 1863. By the end of the century, most of the Europe vineyard was destroyed by the bug. The production of wine has been divided by four. And Europe was not the only area to be devasted by the plague, phylloxera devasted South Africa, California, part of Australia, and even China.

There are some solutions, using chemicals like carbon disulfide or drowning the vines under a layer of water in winter. But each method was too costly, ineffective, or impractical.

The solution, come, like the little bug, from the USA, grafting the vegetal part of the European Vinifera onto a resistant American Vitis Aestivalis. The root does not change the nature much of the vine, it acts like a transit medium for water and nutrients. The European vineyards were replanted using this hybrid plant but not without consequences. The first one was the change in the vineyard geography; vines were replanted in a row to allow mechanization. The second one is the quasi-disappearance of several ancestral grape varieties.

Another consequence was driven by the demand for wine. At this time wine was more a nutriment than a beverage. It was consumed daily. The demand did not change during the phylloxera crisis. So, it opens room for fraud. Adding sugars and water, referment the lot. And, as the newly planted vines were young and productive, too much wine flowed through the market and prices plunged creating a new crisis in the winemaker world.

In France, the crisis ended with large protests. On the 20th of June 1907, five people died during a demonstration in Languedoc. Demonstrators asking for the end of unfair practices under the watchword, “Vive le vin Naturel” (Long live natural wine).

Large protests occur in the Champagne region against the usage of wine from other regions to create Champagne.

This is the start of a new area; defining the wine and the winemaking process and defining what was possible in a defined wine area. The embryo of what we know today as “Appelation d’Orgine Controlée” was created in 1919, with the delimitation of wine regions, and in 1935 with the ancestor of what we know as AOP (Protected designation of origin) in Europe.

But at the same time, this new area was also the age of chemistry and mechanization, with high usage of fertilizer, pest control, and additives. Wine become more and more of an industrial product, dominated by few grape varieties and sold in supermarkets.

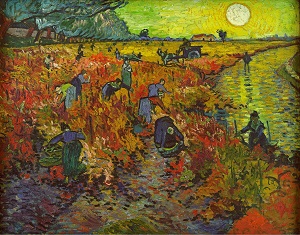

In opposition, during the sixties in the Beaujolais terroir, in France, a new movement was created by a few winemakers as a reaction to the increasing industrialization of winemaking practices, which included the use of synthetic chemicals and additives. They wanted to seek to return to more traditional methods and create wines that were true expressions. The movement gained popularity outside the Beaujolais in France, particularly in regions such as Loire Valley, and Languedoc-Roussillon. The term “vins naturels” became associated with this style of winemaking, and the movement gained international recognition. Natural wine promotes a more artisanal approach where winemaking can be considered an art valuing individuality, terroir, and authenticity.

This idea to get back to more artisanal style winemaking came also with the idea to relive some old grape varieties that were judged not productive enough. In France, even if there are more than 300 varieties authorized (some of them are very recent hybrids). In France alone, Grenache noir, Carignan, Cabernet Sauvignon, Pinot noir, Ugni blanc, Sauvignon blanc et Chardonnay cover more than 65% of the vineyard. Some grape varieties are only present on less than 2 hectares or worst are only present in research institutes. The return to more traditional winemaking is linked to the revival of rare and local grape varieties. Either by exploiting vines that survived the phylloxera plague or by replanting these rare varieties either with American roots or Vitis Vinifera roots (Franc de pied). Natural winemakers reveal the authenticity of the terroir in France and other countries.

![]()

Let’s take some examples. Grolleau, traditionally used to produce rosé, is used to create light, fruity, and fresh red wine. Fer Savadou, in the southwest of France, used only by a few winemakers is more easily found among natural winemakers in Aveyron, Cantal, and in the Lot region. It is used to create light or full-body red wine. Persan in Savoie, a near-extinct variety, experiences a resurgence thanks to natural winemakers.

The phylloxera crisis that started in the late 19th century is among these events that changed the world of wine for the bad and the good. It modeled the wine as we know it today. It helped to create a strict réglementation and more protection for terroir. But it’s also paved the way for industrial wines and mass consumption. But at the same time trigger a reaction that is linked to the natural wine movement.