Behind terroir

Terroir is one of the most frequently used French terms in the wine world. But what does it truly mean? What lies behind this concept?

The online edition of the dictionary from the French Academy, defines terroir as: “A more or less vast area of land characterized by a set of properties linked to the nature of the soil, the climate, and the relief.”

When it comes to wine, the definition of terroir become a more complex concept. The term itself is a portmanteau, evolving in meaning depending on who discusses it. It resonates emotionally with those who appreciate wine, shaping their understanding of what gives a wine its identity. So, what truly lies behind terroir?

To grasp this idea fully, we must first explore the history of wine; and how it has shaped and been shaped by terroir over the centuries. Then, we can examine the various interpretations of terroir, followed by a deeper discussion of the factors that create it.

The relationship between vineyards, specifically their location, and wine quality is deeply rooted in history, dating back as far as the origins of winemaking itself.

Archaeologists discovered a clay tablet in present-day Syria, dating back 4,000 years. On it, a complaint was written about the lower quality of a batch of wine from a specific region, Armenia. This provides early evidence that the link between geography and wine quality was already recognized at the time. Certain flavors and levels of quality were expected from wines produced in specific regions.

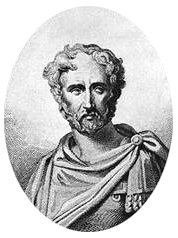

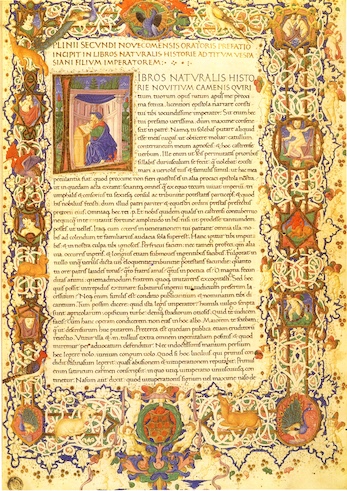

Pliny the Elder was likely the first author to formally document this connection. In his masterpiece, Naturalis Historia,the Book XIV is dedicated to vines and wine. He wrote about the concept of terroir, or rather, its Latin, Territorium, referring to places known for producing high-quality wine.

The same Latin word later evolved into terroir in the 13th century, used to describe a region where agricultural products shared distinct qualities, shaped by their environment.

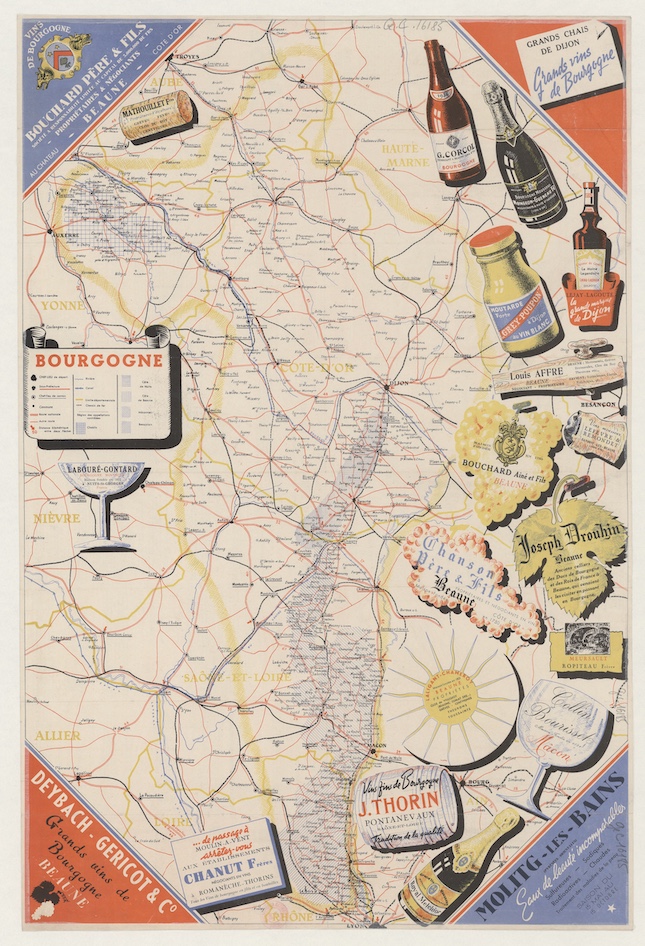

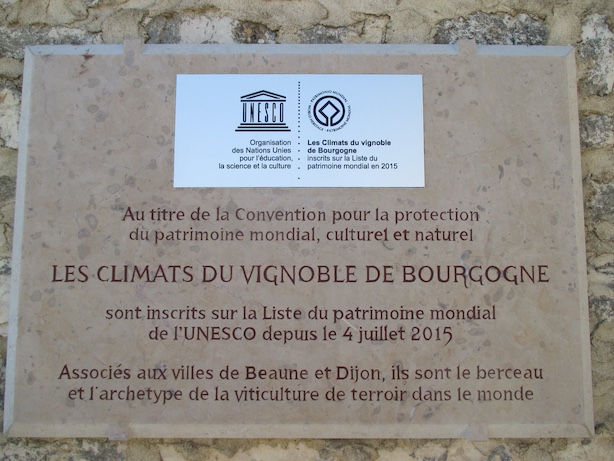

Another earliest use of terroir in the wine world was to describe the quality of wines produced in Burgundy, particularly the renowned vin de Beaune.

However, terroir is not simply a synonym for territory (Territoire in French). Unlike a mere geographic designation, terroir inherently involves human intervention through the planting of grapevines, winemaking techniques, and the delicate interplay between place, grape variety, and craftsmanship. It is a fundamental concept in rural geography, reflecting the dynamic relationship between nature and human expertise in viticulture.

The origin and history of the word terroir provide context, but they do not fully reveal its meaning. Within the wine industry, terroir carries profound significance.

The most common interpretation, especially among non-French speakers, is the sense of place. It translates the essence of terroir, reflecting how a wine embodies the flavors and character of the region in which it was made.

Consider Beaujolais: though vintages and producers may vary, certain defining characteristics remain consistent across Beaujolais wines. These elements distinguish a Beaujolais from a Gamay produced in the Loire, despite both sharing the same grape variety. The same principle applies to a Sauvignon Blanc from Sancerre versus one from New Zealand or a Pinot Noir from Bourgogne compared to one from Jura or Alsace. Terroir is what makes each of these wines unique, shaping their identity beyond grape variety alone.

As the scientist and wine writer Jamie Goode (1) notes, do we truly taste the terroir, or is it merely typicity? A wine may reflect the characteristics of its winemaking region due to shared production methods rather than an inherent expression of place. Alternatively, do winemakers deliberately use techniques that best complement the natural potential of the region?

In this case, the balance between natural geography and human intervention leans more toward human influence, shaping the final identity of the wine.

Another widely accepted definition of terroir focuses primarily on geography. In this view, terroir is the sum of soil composition, rock formations, and climate. This notion is particularly evident in Bourgogne, known for its Climats de Bourgogne, as well as Bordeaux, where the concept of terroir is deeply embedded in viticulture. Under this definition, the characteristics of the soil and the local microclimate play a greater role in shaping the wine than the winemaker’s techniques. The natural conditions influence the fruit’s taste, which in turn defines the wine’s profile.

If soil were the dominant factor in terroir, then theoretically, transplanting soil from one vineyard to another would transfer its unique qualities to the wine. However. Such as attempts to use soil from one of Bourgogne’s Crus in a different vineyard failed to produce the expected results.

This leads to the fundamental question: Do terroirs truly exist? Some argue that the term is increasingly more about marketing than a tangible reality. In France, there have been cases where the prestige of a vineyard’s location carried more weight than the actual quality of the wine it produced.

Moreover, some people argue that terroir no longer truly exists, as the distinctive taste of Bourgogne, Bordeaux, and other renowned and lesser-known regions has changed over time. It is no longer something purely inherent to the land itself… and it is not something we ear from grumpy old people regretting their younger years, it is something you can taste (If you have the luxury to find an old bottle).

So, what has happened to terroir?

I partly grew up in a region where terroir shaped local agriculture, not for wine, but for plums and raspberries. Their taste was remarkable, impossible to compare to supermarket produce. On one side, there is a centuries-old tradition—organic methods, and careful harvesting at peak ripeness. On the other hand, industrial agriculture is optimized for mass production. Could this be the reason behind the supposed decline of terroir?

Scientific research has sought to uncover the essence of terroir; what makes a place, beyond winemaking techniques, impart a unique taste. Jules Chauvet(2), a wine merchant and scientist, conducted extensive studies on the wild yeasts of Beaujolais. He found that the taste variations between different villages, or terroirs, were partially influenced by differences in native yeast populations.

Another key factor is soil, not just its composition, which matters, but not as much as once thought. The crucial element is how vine roots interact with the soil. If the soil is too rich, the wine becomes bland and lacks character. Instead, vines must be grown in relatively poor soils, where stress forces the roots to dig deep, concentrating flavors in the grapes. The deeper the roots search for nutrients, the more distinctive and refined the wine becomes.

Another crucial aspect of terroir is the relationship between vine roots and the soil. A complex symbiosis exists between fungi and roots, enabling vines to extract more nutrients from the earth.

This interaction may help explain why some believe terroir is fading. Industrial yeast, fertilizers, and phytosanitary treatments are often blamed for taste standardization, diminishing the unique imprint of place on wine. Yet, terroir has not disappeared entirely, its essence can still be found in natural wines, which avoid these artificial interventions.

And to finish, do we still use terroir as a guiding factor in wine selection? Among wine professionals and many enthusiasts, the winemaker’s name often takes precedence, along with their stylistic approach and previous collaborations. We first consider the winemaker, then the style, whether light or bold, fruity or restrained, and only afterward the terroir, as a means of contextualizing taste. Terroir remains significant, but perhaps less influential than we once believed, Terroir has become a tipicity marker.

(1) see Jamie Goode, The Science of Wine – from Vine to Glass – 3rd Edition, University of California Press. (2) check this previous post natural wine: from the origin